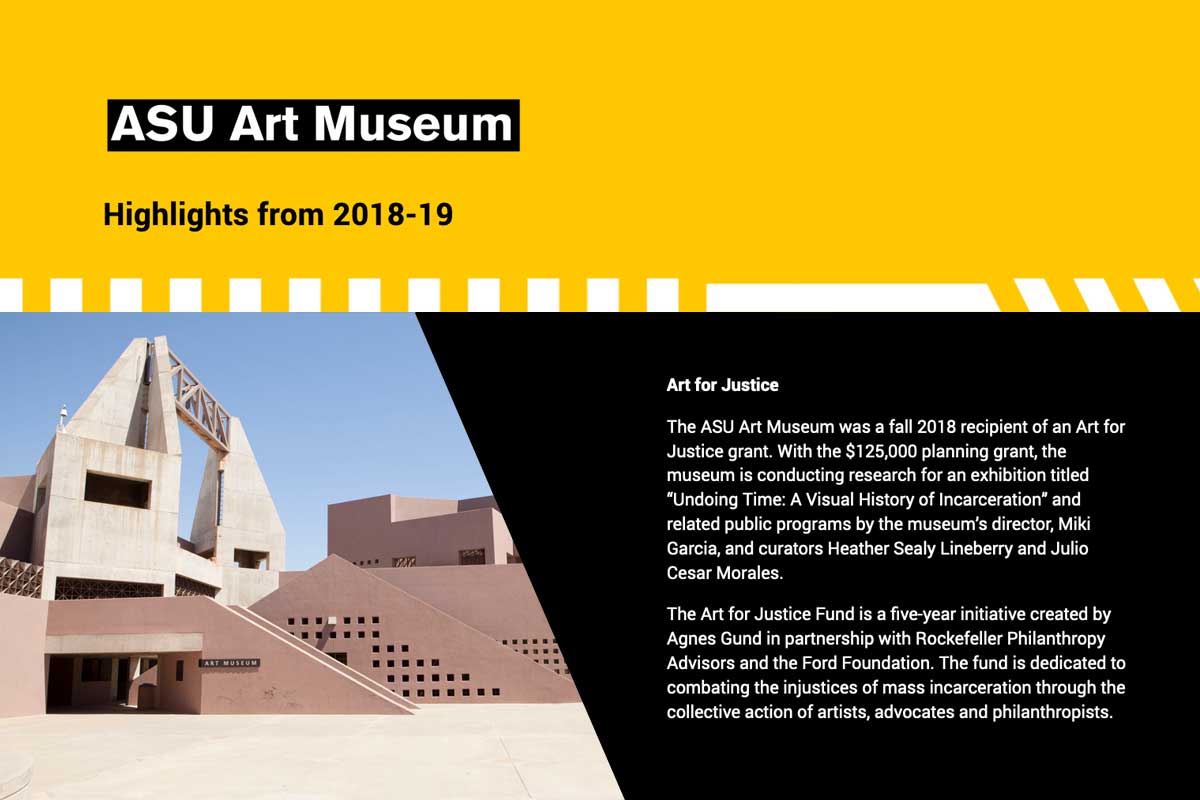

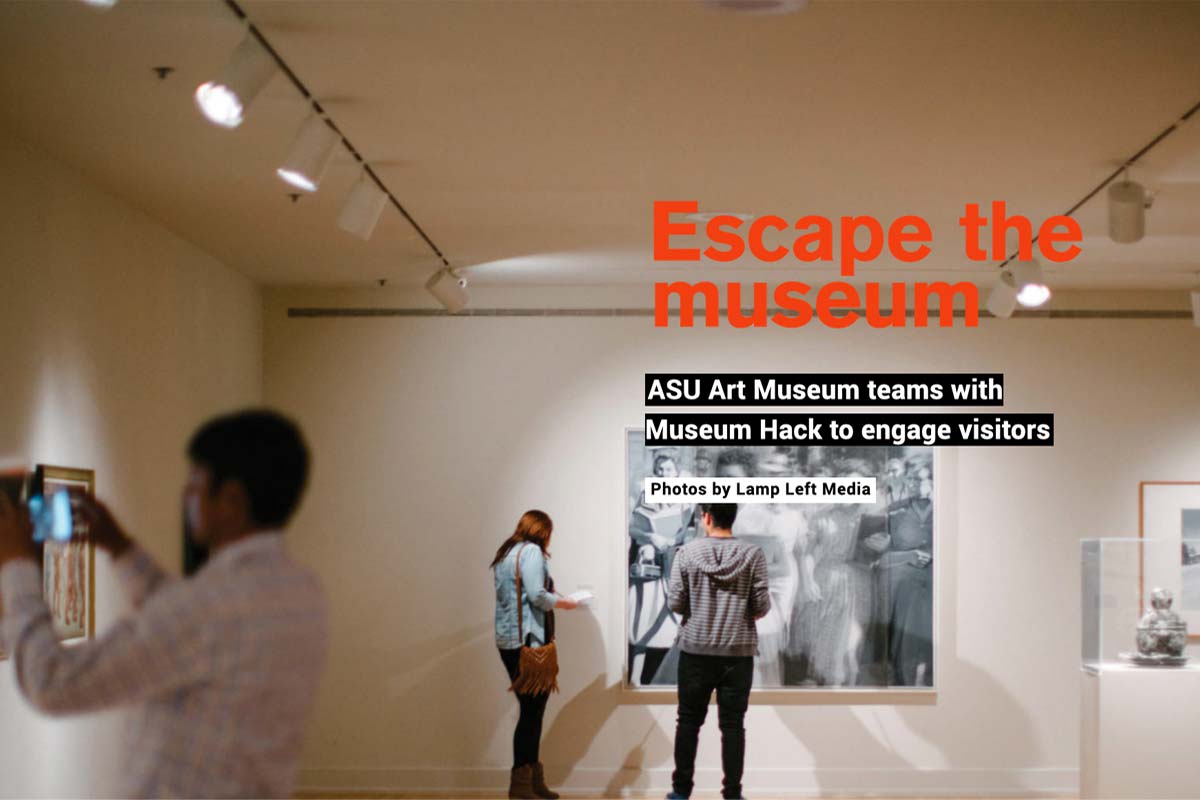

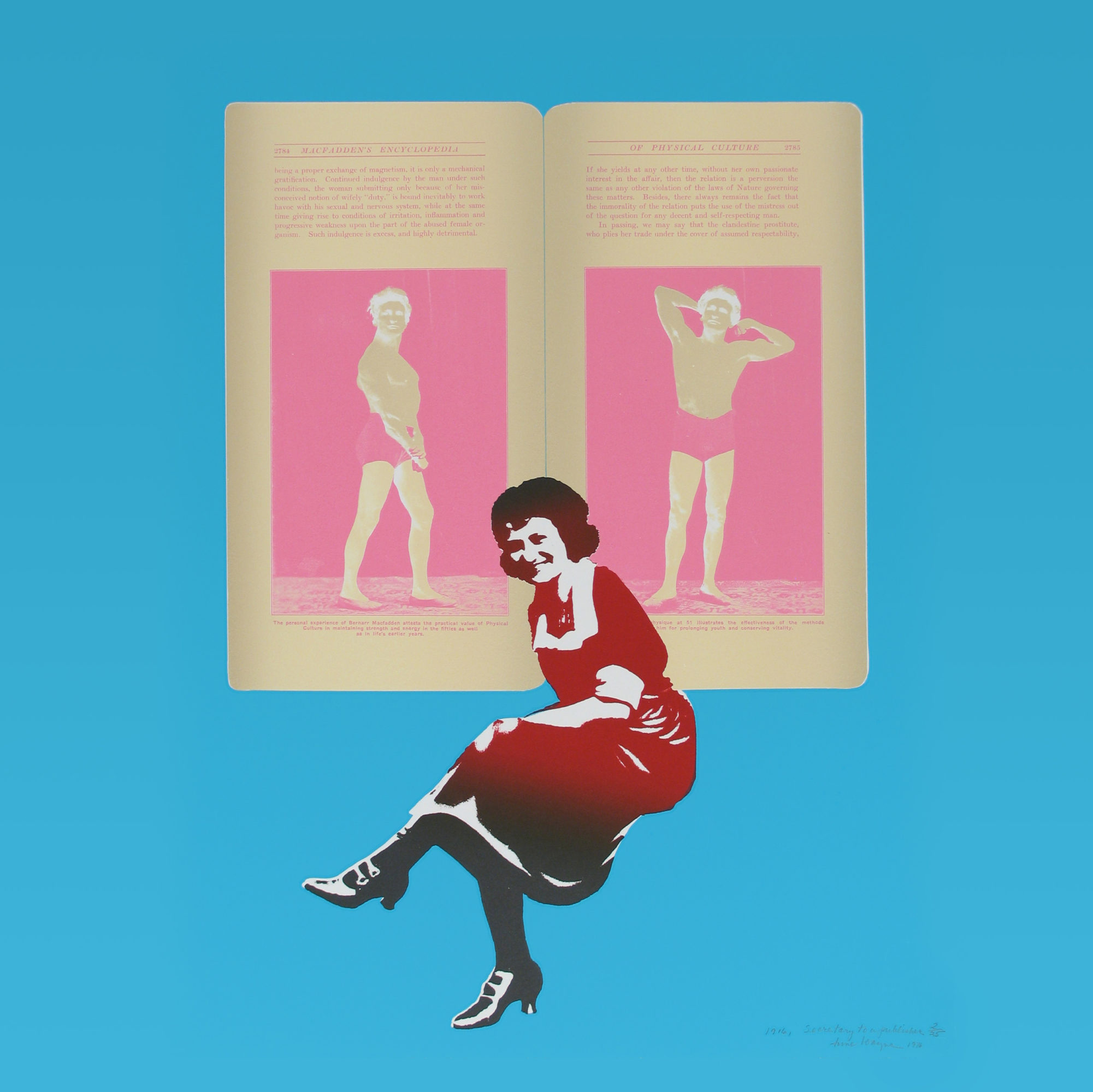

A 2019 data survey of the permanent collections of 18 prominent art museums in the U.S. found that out of over 10,000 artists, a mere 13% are female. The ASU Art Museum is at the forefront of an effort to shift that number and boost the recognition accorded women artists. Two shows this past year, in particular, shone a spotlight on works by women in the museum’s extensive permanent collection: “Change Agent: June Wayne and the Tamarind Workshop” and “Clayblazers: Women Artists of the ’50s, ’60s and ’70s.”

“Both of these exhibitions, drawn from the strength of the ASU Art Museum’s permanent collection, highlight the underrecognized contributions of women to art of the 20th century,” said ASU Art Museum Director Miki Garcia. “Our curators have pulled together works by important artists to be recognized among their peers – an important and overdue correction to the canon.”

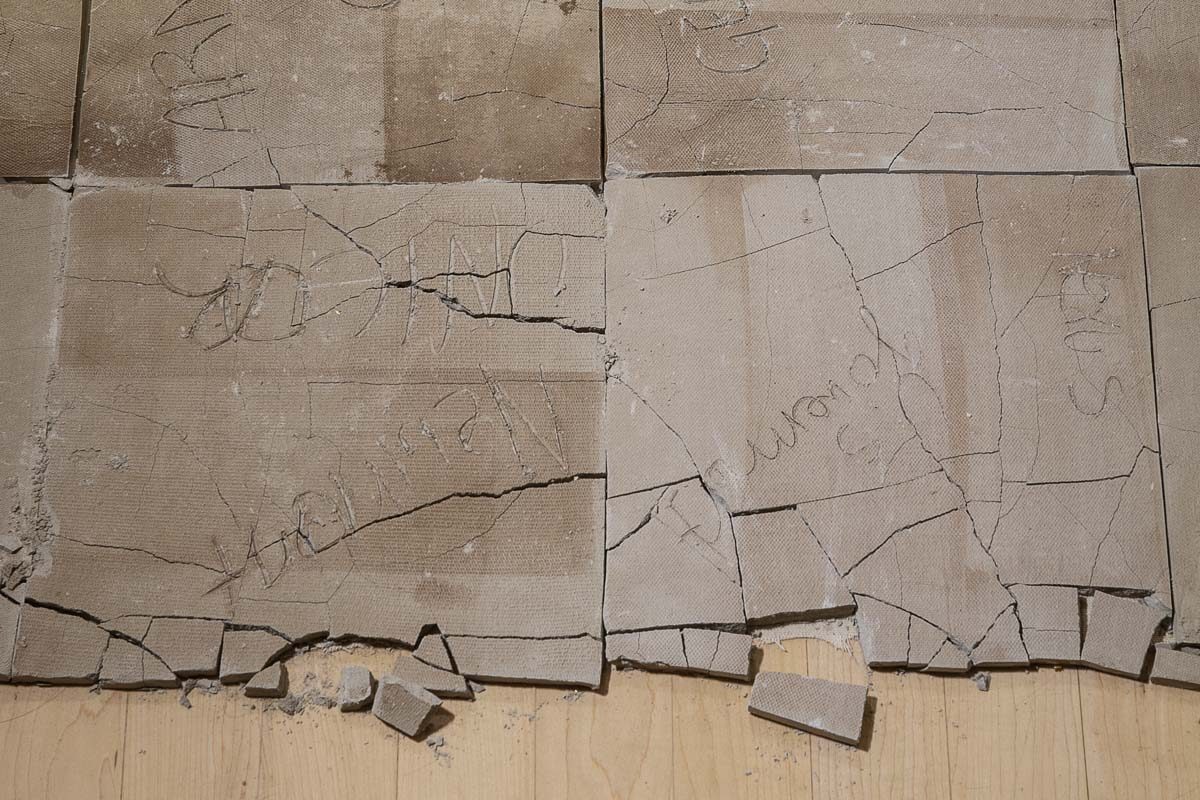

June Wayne was a significant American artist in her own right who devoted her attention to ensuring the resuscitation and survival of lithography, which is the process of printing from a flat surface — usually stone or metal — treated so as to repel the ink except where it is required for printing. In 1960, when Wayne secured a Ford Foundation grant to establish Tamarind Lithography Workshop in Los Angeles, lithography was on the verge of extinction in the U.S. Wayne compared artist-lithographers to the great white whooping crane, in need of “a protected environment and a concerned public so that, once rescued from extinction they could make a go of it on their own.”

“When June got started, the attitude was ‘real artists don’t make prints,’ ” said Marjorie Devon, director of what is now the Tamarind Institute in Albuquerque, in a 2006 interview with The Los Angeles Times. “It’s a testimony to her persuasiveness that she got top artists interested.” The experimental workshop created a pool of printers and apprentices, as artists from across the country were invited to master the process of lithography. Today the Tamarind Institute, part of the University of New Mexico, continues Wayne’s visionary plan as a major training center for fine art printers.